Older People: How can we do it?

Actions to take

-

Review the recommended general actions. This includes information about raising awareness and partnership working. See also additional related guidelines associated with older people in ill-health.

-

Make use of registers which are already held within local authorities and organisations with a role in service provision. Data sharing requires relevant approval, but subject to that being received, organisations involved in emergency planning could make use of local authority data on older people receiving care and other types of support in order to ensure that their needs are appropriately considered.1

-

Consider how registers and other information resources can be kept up to date and responsive to changing circumstances, such as in relation to the threats shown in Figure 5 (in Section 4 above). Social networks and community groups may be important sources of information about changing personal circumstances.

-

Consult guidance about how to incorporate climate change impacts into risk registers and other key strategies including local Joint Strategic Needs Assessments (JSNAs).

- While protecting the needs of the most sensitive and vulnerable people, older people more generally can be engaged using a range of methods. Recommendations originally developed to help improve general engagement with older people2 and for meeting carbon reduction targets can be applied to activities for raising awareness and developing actions in relation to the impacts of climate change and extreme weather3. Indeed, actions on climate mitigation and adaptation could usefully be considered together.

- Abandon old stereotypes – not all older people are unable to help themselves or disinterested in doing so. Older people are not only potentially at risk but may also be campaigners for and contributors to tackling the problem of climate change itself4. A well rounded and joined up adaptation plan will recognise threats but also opportunities for action involving different older groups. More information is available here.5

- Get to know your target audience – consider the range of personal and social characteristics associated with older people that affect their behaviour and take account of varying interests and outlook. It may be helpful to consider differences in experiences, perceptions and outlooks between people aged 50-64, 65-74 and over 75 years of age, while still recognising that these are also extremely disparate sub-groups6. For example, the relative importance of what gives people a good quality of life could also differ between people with different ethnic and social backgrounds.7

- Use trusted intermediaries – information tends to be better received and accepted if delivered by local and well established community groups or recognised authorities, such as GPs8, local leaders (e.g. Councillors) and the emergency services. Peer-to-peer and family networks and neighbours may also be particularly well placed to help with some aspects of preparing for and responding to events.

- Use peer to peer communication – existing social networks have a vitally important role and can be very effective when provided with the correct information if this is delivered clearly and unambiguously.

- Use positive messages – accessible forms of actions and easy tips which stress positive outcomes can help to encourage behavioural change.

- Use the right “frames” – information can be more acceptable if it is related to contexts which are meaningful for the particular individuals and groups. This might consider appropriate terms such as thrift, family and community for motivating preparatory action. Reducing burdens for the next generation can also be a powerful motivator for action given that more than 80% of people believe that their grandchildren will face bigger problems from climate change than they do9. This is applicable to preparing for impacts as well as for reducing carbon emissions.

- Show real life examples – examples of what other peers have done can be helpful. Information can be delivered in places like shops, health centres, community centres and religious institutions. See the Further Resources section for a set of case studies relating to older people.

- Develop an inclusive dialogue – often concerns and misconceptions only emerge through discussion with individuals and specific groups and not always through individuals who work with older people in a professional capacity.

- Maximise participation – events need to be tailored to the audience including through considerations like timing, format and the safety and accessibility of venues. Face-to-face engagement can be important (whether directly or through community groups) since some older people are unlikely to access materials via the internet. Appropriate resourcing for face-to-face engagement is also important for some participation. Working with carers may be important for supporting the engagement of older people with higher support needs.

- Ensure the setting is right for change – the adaptive capacity of older people may be reliant on community services without which self-help is extremely difficult.

- Make use of specific guidance for raising awareness among older people. There are various sources of information which can be used to help develop personal plans:

- The Blue Cross provides information sheets about Pets and Flooding based on Environment Agency guidance.

- The Environment Agency produces flood guidance targeted at older people which is also promoted by AgeUK.

- Public information is available to promote self-help for preparing for heatwaves and to recognise early signs of the impacts of over-heating, such as dehydration.

- Consider how staff training events can be used to build up knowledge of the issues.

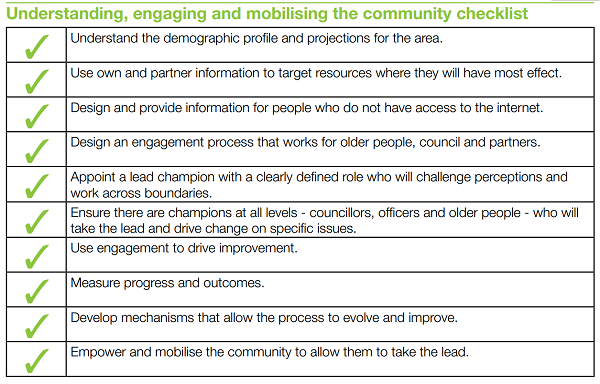

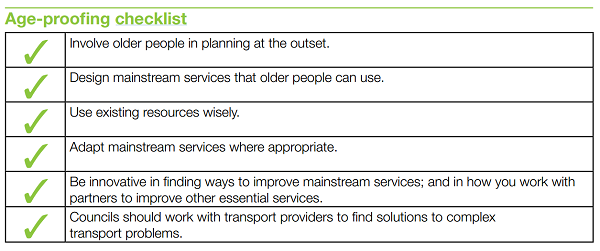

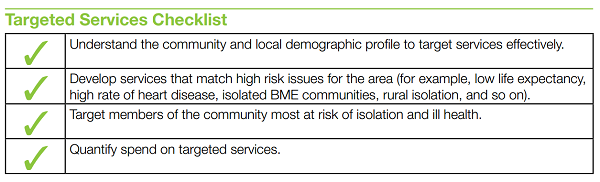

- Promote the use of existing checklists for age-proofing mainstream services, engaging older people and targeting services (Figure 6).

- Review the work of the Vulnerable and Older People Advisory Group

Figure 6: Checklists produced by the Audit Commission10.

- Consult guidance about the particular needs of older people after a flooding event has occurred. A set of considerations and possible actions to address the ‘recovery gap’ more broadly can be found here11, including:

- Single points of contact and dedicated local teams to help to deal with issues like insurance claims and managing remedial work.

- Contact points and advice services advertised in local media and warning systems which use a range of communication methods.

- Continuity of service provision and providers during the recovery process, even if people need to be physically relocated. Some older people can find such changes difficult and stressful to manage.

- Statements of principles with landlords, estate agents and utility companies.

- Support for continuing networks after initial recovery phases, e.g. through provision of meeting spaces.

- Work in partnership with others. Partnership working is a crucial part of any response to the challenges of climate change and extreme weather. Workshops are one way through which improved dialogue can be achieved, but in order to make meetings as effective as possible it is important to involve all relevant organisations.

- See the Further Resources section for a link to an example of who to involve. A list of organisations that should be considered is provided in the ‘Under the Weather’ toolkit. Local Resilience Forums also provide a good basis for collaboration and dialogue and provide a foundation for understanding pressures and opportunities across a range of organisations with shared goals and related responsibilities.

- Also see Benefits of partnership working.

- Support and encourage local organisations to work with the voluntary and community sector to raise awareness of climate risks and promote personal adaptation strategies. Where possible, this should build on existing programmes and voluntary sector initiatives and pay particular attention to reaching marginalised communities. Some areas may have well developed community organisations, facilities and networks which can be used to disseminate good practice and promote appropriate self-help alongside responses delivered through social services. Dialogue with friends, neighbours and family are also important, especially since such networks are highly influential and can help to proliferate inaccurate or out-of-date information12. Neighbours can be an extremely important source of help but older neighbours can be overlooked in the stresses of dealing with the challenges of events like flooding13.

- See the Further Resources (Section 6. Above) for links to relevant case studies such as:

- The Snow Angels initiative. This aimed to reduce the physical and social isolation of sensitive individuals during cold weather but ideas could be extended to consider needs during other extreme weather events.

- NCVO’s work with older people as part of their Vulnerable People and Climate Change project.

- Use existing processes and good practice guidelines to help draw up adaptation plans for health and social care organisations.

- See the Sustainable Development Unit’s information about the characteristics of a good adaptation plan in health and social care. Also see People in poor health.

- Ensure that preparedness for extreme events includes relevant infrastructure, such as buildings which are important for delivering health and social care so that patients and staff are protected from the impacts of events like heat-waves and flooding14. Such buildings include hospitals, clinics and health centres, doctors’ surgeries, care centres, residential care and nursing homes, day centres and general care facilities.

- Explore ways in which changes can be made in how and where people work, the codes of practice used and the sorts of systems used to deliver services. Relatively simple back up measures may be helpful, such as the use of telephone follow ups in place of appointments if patient access is an issue during extreme events15. Telehealth and Telecare may also offer some opportunities.

- Consider how adaptations can be made in care homes with the help of residents. For example, this may involve setting up agreements about areas within care homes which can be designated ‘warm’ or ‘cool’. This could also apply more generally in public buildings, like libraries.

References

- Houston, D., Werritty, A., Bassett, D., Geddes, A., Hoolachan, A. & McMillan, M. (2011) Pluvial (rain-related) flooding in urban areas: the invisible hazard, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York.

- Audit Commission (2008) Don’t stop me now. Preparing for an ageing population Local government National report July 2008

- Haq, G., Brown, D. and Hards, S (2010) Older People and Climate Change: the Case for Better Engagement Stockholm Environment Institute, Project Report – 2010

- Haq, G., Whitelegg, J. and Kohler, M (2008) Growing Old in a Changing Climate Meeting the challenges of an ageing population and climate change

- Audit Commission (2008) Don’t stop me now. Preparing for an ageing population Local government National report July 2008

- Haq, G., Whitelegg, J. and Kohler, M (2008) Growing Old in a Changing Climate Meeting the challenges of an ageing population and climate change

- Bajekal, M., Blanc, D., Grewal, I., Kurslon, S. and Nazroo, J. (2004) Ethnic differences in influences on quality of life at older ages: a quantitative analysis, Ageing & Society, 24, 5, 709–28

- Lindley, E. et al (2012) Improving Decision-Making in the Care of Older People: Exploring Decision Ecology

- Haq, G., Brown, D. and Hards, S (2010) Older People and Climate Change: the Case for Better Engagement Stockholm Environment Institute, Project Report – 2010

- Audit Commission (2008) Don’t stop me now. Preparing for an ageing population Local government National report July 2008

- Whittle, et al. (2010) ‘After the rain: Learning the lessons from flood recovery in Hull’, final project report for Flood, Vulnerability and Urban Resilience: A real-time study of local recovery following the floods of June 2007 in Hull. Lancaster: Lancaster University

- Wolf, J., Adger, W. N., Lorenzoni, I., Abrahamson, V. and Raine, R. (2010) ‘Social capital, individual responses to heatwaves and climate change adaptation: An empirical study of two UK cities’. Global Environmental Change, 20, pp. 44–52

- Preston, I, Banks, N, Hargreaves, K. Kazmierczak, A, Lucas, K Mayne, R Downing C and Street, R (2014) Climate Change and Social Justice: An Evidence Review Joseph Rowntree Foundation

- NHS Sustainable development Unit (2012) Adaptation to Climate Change for Health and Social care organisations “Co-ordinated, Resilient, Prepared”.

- NHS Sustainable development Unit (2012) Adaptation to Climate Change for Health and Social care organisations “Co-ordinated, Resilient, Prepared”.

Built by:

© 2014 - Climate Just

Contact us